Fetch - Modern Async Server Calls

Being a web developer right now is exciting and confusing. We keep getting new tools, but they all seem to come with more tools of their own.

It’s refreshing when we get a near-total replacement for something that is actually simpler. XMLHttpRequest (XHR) is the definition of an old, confusing, complex tool. Fetch API is the simpler replacement.

Fetch vs. XHR?

Fetch is a brand new way of making asynchronous calls to the server. Before we dive into the details, let’s look at an example of Fetch versus XHR. To make this simple, we’ll just request a file (jQuery in this case) from the Google CDN and just dump it to the console.

Fetch Example

// Loading the jQuery code

fetch('https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/2.1.3/jquery.min.js')

.then(function (response) {

response.text().then(function (responseText) {

console.log(responseText);

alert('Done using Fetch!');

});

});

Now, let’s take a look at this using XHR.

XHR Example

// Loading the jQuery code

request = new XMLHttpRequest();

request.open("GET", "https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/2.1.3/jquery.min.js", true);

request.send(null);

request.onreadystatechange = function() {

if(request.readyState === 4) { // What does this even mean?

if(request.status === 200) {

console.log(request.responseText);

alert("Done using XHR!");

}

}

}

This is a pain to write and read. I had to Google what readyState 4 even meant (request finished and response ready) to write this post. Why do I have to send a null?

In reality, a lot of devs just include jQuery and write this:

$("#basicjQueryButton").on("click", function() {

// Loading the jQuery code

$.get("https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/2.1.3/jquery.min.js", function(data) {

console.log(data);

alert("Done using jQuery!");

});

});

We download 34.5KB (as of 3.1.0), sometimes just for this functionality. You don’t need to do this anymore.

Now There Is Fetch

The Fetch API gives us a generic Request and Response that we can use to GET/POST/PUT/DELETE/HEAD data to and from the server. It uses promises which makes it easier to code, as well as much easier to read. Because it is promise based, it even chains nicely into other methods.

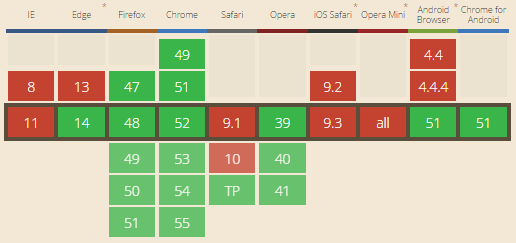

It’s useable today in Chrome, Edge and Firefox, and other browsers through a polyfill.

Promises?

Before diving into the advanced features of Fetch, let’s take a brief look at promises. If you want to learn more, I recommend this really excellent post from Jake Archibald.

Promises are a new way of dealing with asynchronous code in JavaScript that are simpler than chains of callbacks. Promises make it easy to write code that reads like human language. For example, you could write something like this:

LoadMyData()

.then(ProcessMyData)

.then(DoSomethingElse)

.catch(HandleError);

There is a lot more to promises, but for this article you should know the following:

- Promises start off pending

- Promises resolve as either fulfilled or rejected

- Fulfilled promises trigger a .then() call

- Rejected promises trigger a .catch() call

- All of this happens asynchronously, when the previous promise completes

Request & Response Object

The example shown above defaulted to a simple GET and didn’t set any advanced headers. However, Fetch allows you advanced control of your Request object before making a request, and lets you query the Response object after. For example, say your application wants to do the following:

- Make a CORS request to a remote server (in this case, the very handy reqres.in)

- Specify that you’re looking for a content type of “application/json”

- Make sure you don’t check cache or store the response in it

- Verify you got JSON back from the server (or maybe choose how to parse based on the data)

var headers = new Headers();

// Set the content type to JSON

headers.append("Content-Type", "application/json");

// Setup GET and disable cache

var init = {

method: "GET",

cache: "no-store",

mode: "cors",

headers: headers

}

fetch("http://reqres.in/api/users", init)

.then(function (response) {

// Check that the response is a 200

if(response.status === 200){

alert("Content type: " + response.headers.get("Content-Type"));

}

});

Stream Readers

You may have seen a call like this above:

response.text().then(function (responseText) {

console.log(responseText);

alert("Done using Fetch!");

What I didn’t tell you before was that .text() is actually a stream reader. The TL;DR of this is that the response data is a stream of bytes that you can read from. Stream readers pull in the entire stream and parse it for you.

There are a few methods available to you including:

- .text() - returns the full stream as a string

- .json() - returns a JSON object

- .formData() - returns a FormData object, which may be useful for posting somewhere

- .blob() - returns the stream as a blob, useful if you may do non-JS parsing with it

- .arrayBuffer() - returns an array buffer. This may be useful for streaming

If you need to parse the stream twice it’s a problem, because once you’ve read it, it’s empty. Fortunately there’s one more method:

- .clone() - creates an identical copy of the response

Alternatively, you can parse the string manually and do what you want. You can find a good example here (with source), but note that this doesn’t work in all browsers yet.

What’s the Catch?

Fetch can do nearly everything that XHR can do. The two things that are missing:

- Fetch requests can’t be canceled. This seems largely due to promises not being cancelable. Luckily, there’s a spec in draft for that.

- Progress is difficult to track. You have to build that yourself. You can see an example of that here from this article from the Edge team.

That’s really it. I told you this was a big improvement!

Conclusion

Fetch is a powerful tool you can use today (with or without the polyfill), and it’s better than XHR for almost any application. You probably weren’t writing XHR yourself, but if you were, life just got better. It’s more likely you are using a library like jQuery to simplify your AJAX calls which won’t be the case anymore. If you want to take a deeper dive into Fetch, the Mozilla Developer Network is the place to start.

Fetch really comes into its own when we start looking into Service Workers, but that’s a topic for another post.

Happy coding!